When I heard painter Françoise Gilot died last week at the age of 101 I thought: “What a life.”

Growing up in Paris, she began painting as a child and continued into her late 90’s. Her work, which is found at major museums, galleries and auction houses around the globe, can command seven figures.

She travelled the world, raised three children1 and was married to Dr. Jonas Salk, (until his death in 1995) the medical researcher who developed the first polio vaccine.

But in most of the obituaries, the headline leads with the relationship that has defined Gilot in the public’s imagination for the past eighty years—the decade she spent as the partner of Pablo Picasso.

It’s the 50th Anniversary of Picasso’s death and there are events marking this in a variety of ways, including a controversial show at the Brooklyn Museum that has been all over the news. Picasso continues to be a brilliant and polarizing figure a half-century after his death.

Françoise Gilot did what none of Picasso’s other partners had done. She left him.

When, after ten years and two children together he continued to be unfaithful, she no longer loved him. Enraged, he did everything he could to undermine her relationships in the art world and beyond.

Then, in 1964, Gilot wrote the unapologetic memoir, Life With Picasso. It was a success and a scandal and Picasso tried desperately to block its publication with three different lawsuits, all of which failed.

He congratulated Ms. Gilot after she prevailed a third time, seeing her as a worthy adversary that in his mind reflected well on him.

In the memoir, Ms. Gilot presents Picasso in full. He is one of the world’s most important artists and he can be a monster. He is both loving and cold. He flies into cruel rages and is gentle — by turns generous and withholding. He is supremely confident and also jealous of the fondness she has for Matisse, whose work she prefers. She grows to love Picasso deeply but he cannot meet her desire for more affection and fidelity.

They are joined in their belief that making art is like needing air. One cannot live without it.

It’s a fascinating read and has been lauded as one of the best books to offer a glimpse into the mind of Picasso. Ms. Gilot is formidable and she is Picasso’s intellectual equal and then some.

At the Beginning, Offering A Bowl of Cherries

On the opening pages of Life With Picasso, Gilot describes a scene so electric, so specific, you feel you’re spying from another table at the restaurant Le Catalan in Paris to see how it unfolds.

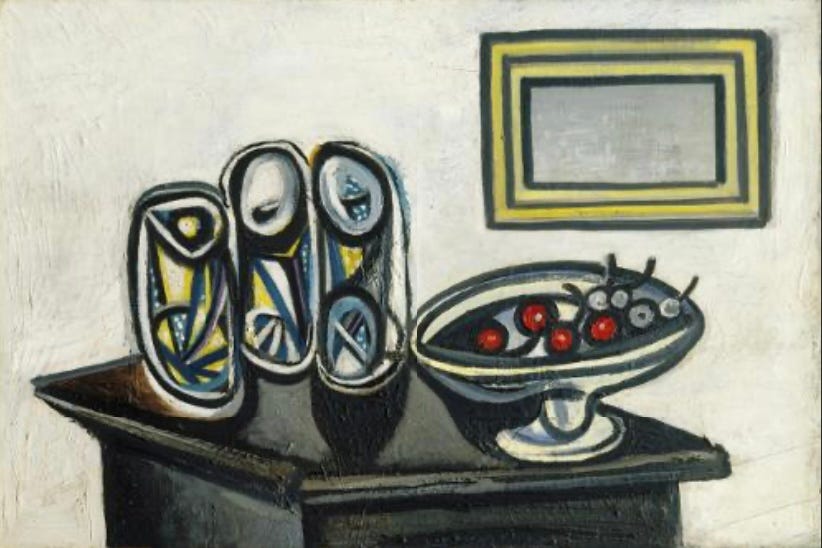

It is 1943 in occupied France, all emotions heightened by war. The twenty-one-year old Gilot had been arrested at a demonstration, but released. She is having dinner with friends. At the next table, Picasso is dining with his partner and subject of his paintings, Dora Maar.

Before too long, Picasso walks to Gilot’s table, carrying a bowl of cherries and introductions are made. She makes a point to say that he draws out the “s” sound in the word “cerisses” as he offers them around. His offering of the symbolically sensual fruit and the tone of the encounter is clearly not lost on her. Picasso invites everyone to visit his studio soon. He retreats, but Gilot tells us not before taking the bowl of cherries away with him. Picasso giveth sweetness and taketh away.

She begins to visit him and after six months they become lovers as she knew they would.

A friend warns Gilot that she is headed for catastrophe.

I told her she was probably right, but I felt it was the kind of catastrophe I didn’t want to avoid.

— Françoise Gilot, Life With Picasso

Gilot dedicates her memoir “To Pablo” and ends it with this:

Pablo had told me, that first afternoon I visited him alone, in February 1944, that he felt our relationship would bring light into both of our lives. My coming to him, he said, seemed like a window that was opening up and he wanted it to remain open. I did, too, as long as it let in the light. When it no longer did, I closed it, much against my own desire. From that moment on, he burned all the bridges that connected me to the past I had shared with him.

But in doing so, he forced me to discover myself and thus to survive. I shall never cease being grateful to him for that.

— Françoise Gilot, Life With Picasso

There’s a terrific interview with Gilot on her 100th birthday last year conducted by Ruth La Ferla of The New York Times. Here is the link: The New York Times

Cherry Clafoutis and Champagne

It’s always interesting to me how the presence of food in a story, in this case something as small as a bowl of cherries, can pack so much meaning in the telling of it.

Cherries are in the markets so I thought I’d make Cherry Clafoutis, a simple flan-like French dish from the mid-1800’s that’s just as good for breakfast with coffee as it is for dessert with wine or champagne. (The meaning of the word ‘Clafoutis’ is ‘to fill.’ )

With all of the summer berries available you can make all sorts of lovely clafoutis, it’s a quick and easy alternative if you don’t have time to make a pie. I used Julia’s recipe.

Julia Child’s Clafoutis recipe: HERE

The inside is like a cross between cake and a flan. So simple to make and good.

Adieu, Françoise Gilot. ❤️

Have a great week, Everyone.

Jolene

Gilot had two children with Picasso, Claude and Paloma and a daughter, Aurelia, with artist Luc Simon during a brief marriage.

Love clafoutis, which I think sounds especially tempting said in a Scottish accent! 😂 I read somewhere of Bretons making clafoutis "au pif" (following their noses) which means it's a very forgiving recipe. Definitely big dividends for little work!

Great piece, Jolene. I highly recommend Arianna Huffington’s biography ‘Picasso creator and destroyer’ for more on this